GVN Fights Lassa Fever Epidemic in Nigeria

GVN Fights Lassa Fever Epidemic in Nigeria

A PhD candidate at the Institute of Human Virology-Nigeria, a GVN Affiliate, works on Lassa samples.

Outbreaks of Lassa fever used to be limited to northern Nigeria. An acute viral haemorrhagic virus transmitted by rodents, Lassa can cause severe damage to the liver, spleen, kidneys and other organs. For the last few years, though, the virus has spread to other parts of the country and fatalities have increased significantly. This year, the outbreak has been even much worse than usual.

The disease has spread throughout the country, and in just the first three months of 2018 the Nigerian Center for Disease Control (NCDC) had reported 1,613 confirmed cases and 134 deaths. In all of 2016 there were only 79 reported cases of Lassa fever and 35 deaths, and a little more than that in 2017.

Global Virus Network Joining the Fight Against Outbreak

The Global Virus Network (GVN) has joined authorities in Nigeria and other world health organizations to fight against this outbreak. The Institute of Human Virology, Nigeria (IHVN), a GVN Affiliate, and other GVN Centers of Excellence, with expertise in the science of such viruses, have partnered with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Nigerian Center for Disease Control (NCDC) and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) to support fieldwork, surveillance, laboratory diagnostics, contact tracing and prevention education. Using its network of experts and laboratories, GVN has helped to validate simple rapid tests that are being used at rural clinics in villages and to support research to understand transmission patterns and find an effective vaccine.

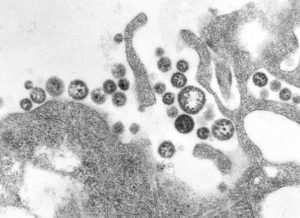

Lassa Fever Virus

“There’s an enormous amount of work to be done,” says Alash’le G. Abimiku, M.Sc, PhD, a professor at the Institute of Human Virology (IHV) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, a GVN Center of Excellence, and executive director of the International Research Center of Excellence (IRCE) at IHVN. “We are doing whatever we can to assist the government of Nigeria to get this epidemic under control.”

Virus, Transmitted Through Rodents, Spreads Rapidly Crowded living conditions and poor sanitation have helped spur the outbreak, especially in densely populated southern Nigeria. Climate change, too, has contributed to the outbreak by creating an environment that allows rodents to thrive year-round.

The virus, which was discovered in the 1950s, is transmitted to humans through contact with food or household items contaminated with rodent urine or feces. It can also be spread between humans — of all ages and sexes — through direct contact with blood, urine, feces, or other bodily secretions. About 80 percent of people who become infected with Lassa virus have no symptoms. But one in five infections result in severe disease.

Because the symptoms of Lassa fever are varied and non-specific, clinical diagnosis is often difficult, especially early on. The incubation period ranges from six to 21 days. Initially, it presents with symptoms — sore muscles, high fever, malaise — that resemble malaria. Patients often take malaria medicine, which has no effect on Lassa. After the incubation period, Lassa can worsen very quickly, causing internal bleeding, seizures, disorientation, hearing loss, coma, and death. The mortality rate for Lassa fever has increased from about five percent to eight percent so far this year. This number may increase still, however, since the mortality rate for 2016 was of 44 percent, with fewer people infected.

Infection Prevention Strategies Key to Controlling Epidemic

Lack of proper infection prevention and control practices in hospitals and among families are the biggest reasons that Lassa fever spreads. Hygiene is key — covering food and grains to keep rodents out, properly disposing of garbage, washing hands and using hand sanitizers, and disinfecting and fumigating surroundings. Family members and healthcare workers must be careful to avoid contact with blood and body fluids while caring for those infected with the virus.

“The problem is that many people do these things very sporadically,” says Dr. Abimiku. “They need to practice consistent, sustained preventative measures.” To promote these simple but effective preventative strategies, the IHVN is supporting the NCDC and the Nigerian government in creating education campaigns.

Ribavirin, an antiviral drug, is an effective treatment for Lassa fever, when given early on in the course of clinical illness. But the drug is very expensive and not always readily available. No Lassa vaccine currently exists, although research is being done on one, with the hope that a vaccine will exist in five years or so.

Lassa Epidemic Showing Signs of Slowing

Dr. Alash’le Abimiku

There is some good news: according to the WHO and Dr. Chikwe Ihekweazu, the national coordinator and NCDC director, the rate of new infections seemed to be slowing as of the end of March. This suggests that public health strategies to promote transmission are having an impact.

“It seems that the epidemic is slowing down,” says Christian Bréchot, MD, PhD, the new president of GVN. “But we have to be prepared for the next outbreak of Lassa or the next viral pandemic that comes our way. We need to be ready.”

Dr. Abimku agrees: “We have to be more proactive. We need to do the research on how transmission works and understand what kind of preventative measures can be put into place before an outbreak, rather than running around after the fact trying to control it once it gets going.